Hatha Yoga and your Energy Body

The ancient hatha yoga texts (Yoga Yājnavalkya1, Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā2, Siva Samhitā3 and Gheranda Samhitā4) describe techniques and practices that have a universal benefit on the human body, energy system, mind and psyche. They are practice manuals, not theological treatises. This may explain hatha yoga’s popularity. It is open to all.

Yoga

Many see yoga as an activity, but it actually refers to a state of complete aliveness, mental clarity, and joy (sat-chit-ananda) where one awakens to the reality of oneself as being divine consciousness. It is a natural state that connects us to all of life and is not dependent upon anything external in order to be experienced.

According to ancient tradition, there are four main paths to attain this state of yoga:

- Karma Yoga - transforming one's actions

- Bhakti Yoga - transforming one's emotions

- Jnāna Yoga - transforming one's intellect

- Rāja Yoga - transforming one's mind

In the Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā, it states that Hatha Yoga is “a ladder to those who wish to attain the lofty Rāja Yoga.”5. It is also said that there can be no Rāja Yoga without Hatha Yoga and no Hatha Yoga without Rāja Yoga.

Rāja Yoga

In Rāja Yoga, we reduce and ultimately stop all mental activity to render the mind completely clear and still. In this profoundly lucid state, we are best able to experience the realisation that our true nature is divine consciousness. In his Yoga Sutras, Patanjali explains that yogis enter this lucid state through a practice of heightened meditative absorption called samadhi. The yogi applies samadhi on more and more subtle aspects of being until he is able to enter into a state of absorption on consciousness itself where he then becomes enlightened.

For those whose minds are not yet prepared for samadhi, Patanjali explains how to cultivate this faculty through Kriya Yoga or traditional Ashtanga Yoga which outlines 8 steps, 5 of which are considered "external" and 3 "internal". Patanjali groups the last 3 "internal" practices together as samyama:

- mental concentration (dharana) where one makes an effort to maintain the mind focussed on an object

- meditation (dhyana) where effort is no longer needed to maintain focus, and

- the state of absorption (samadhi) where one feels no separation from the object of focus

However, as the mind behaves like a wild horse extremely challenging to rein in, mental concentration can prove too difficult. Hatha Yoga allows one to tame the mind indirectly until the mind's refinement through Rāja Yoga becomes possible.

Due to our strong identification with our mind and thoughts, we forget our most essential self and instead become a slave to the mind allowing its desires and thoughts to influence our emotions and behavior. Imagine, for instance, that you fixate on an unfulfilled desire born from the mind that produces feelings of frustration and anger. This fixation agitates the breath and seizes power over you. No lucid thinking can take place. One reacts impulsively in a way that does not bring the best outcome. Instead, it brings trouble.

If we are powerless to move on from anger-producing thoughts by working directly on the mind through Rāja Yoga, we can intervene with the breath using Hatha Yoga to bring the mind into its proper relationship with our deepest self. In a way, Hatha Yoga is the suggestion to take ten deep breaths before acting.

With Hatha Yoga, we work indirectly on the mind by focusing on the purification and channeling of life force energy (prāna) within our energy system, the prānāmāya kosha.

A Focus on Prāna

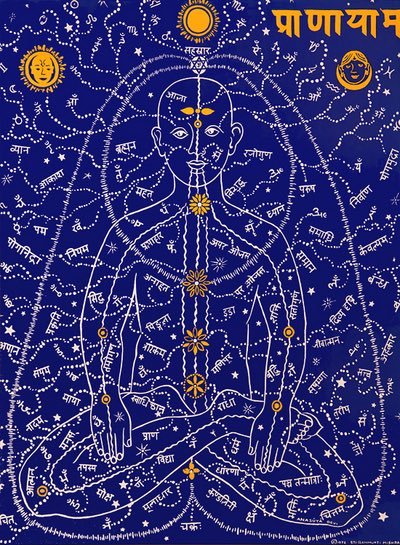

© 1972 Sri Ramamurti Mishra

The life force energy Prāna exists everywhere both within and without the body. External sources include the sun, air, water, food, walking barefoot on the earth, and uplifting social contact.

Within one’s energy system, Prāna circulates in 10 principle ways, 5 of which are considered important with two (prāna & apāna) most important:

- prāna – upward flowing energy associated with inhalation

- apāna – downward flowing energy associated with exhalation and expulsion (reproduction and elimination)

- samāna – digestive energy governing assimilation and absorption

- udāna – energy centered in the throat governing expression and communication, also involved with the upward flow of kundalinī

- vyāna – systemic energy throughout the body governing circulation

Prāna flows through energy channels (nādīs). The ancient hatha texts claim there are 72,000 nādīs but consider 3 most important (idā, pingalā, and sushumnā).

The upward flowing prāna is represented by the “ha” in “hatha”. It is associated with the pingalā nādī along the right side within the spine terminating at the right nostril. The downward flowing apāna is represented by the “tha” in “hatha”. It is associated with the idā nādī along the left side within the spine terminating at the left nostril. Often, these two nādīs are depicted as spiraling and intersecting at six points - the main energy centers or chakras.

When the brain’s creative right hemisphere is dominant, the left idā nādī is more active. Air flows more readily through the left nostril. When the brain’s analytical left hemisphere is dominant, the right pingalā nādī is more active. According to Swara yoga6, either idā or pingalā is more active every 90-120 minutes.

While these energy currents alternate, we experience the concepts of time, space, and ego. However, the great rishis of hatha yoga discovered that through purification of the nādīs (nādī shodhana) and concentration (dhāranā), we can bring the nādīs' flow into equilibrium so that the currents no longer alternate. The prāna and apāna forces flow together through the sushumnā nādī directly between idā and pingalā and are retained there through bandhas and mudrās in a way where the energy is intensified until it sparks the awakening of the spiritual power of kundalinī shakti. After awakening, the practice is to direct the energy upward and maintain it leading to an ecstatic state of transcendence. There is no longer the feeling of time, space and ego. One enters a state of eternity, infinity, and divine consciousness.

Awakening and Rise of Kundalinī

The aim of Hatha Yoga is this joining together of prāna and apāna within the sushumnā nādī. As one advances, the yoga postures and sequencing remain the same, but the hatha yogi takes on a deeper, more intense inner focus within the energetic realm.

Where nādīs cross are hubs or vortexes (chakras) of energy. While the ancient texts claim there are 72,000 nādīs, there are even more chakras of which seven chief chakras are aligned vertically within the sushumnā nādī at points where idā and pingalā are said to intersect.

Some say that kundalinī rises within the sushumnā. Others say that it is “burnt” allowing the conjoined prāna-apāna to rise. In either case, internal blockages or knots (granthīs) of vitality (Brahmā granthī), emotion (Vishnu granthī), and thought (Rudra granthī) are dissolved as this energy rises through the main chakras. It is a union depicted symbolically as a marriage between Sakti (pure energy) who journeys from the base of the spine and Siva (pure consciousness) who resides motionless at the crown of the head (the Brahmarandhra).

Hatha Yoga

Working with the energy system brings tremendous power. Before starting, the hatha yogi abides by certain ethical restraints (yamas) and ethical observances (niyamas) to ensure that this power is deployed in a beneficial manner both for the practitioner and the world. They are also the first steps toward discipling the mind to the will of our deepest self.

Then, the hatha yogi practices:

- kriyās - purification techniques

- āsanas - yoga postures

- prānāyāma - breathing techniques

- mudrās - energy seals

- bandhas - energy locks

- pratyāhāra - sense withdrawal

- dhāranā - concentration

- dhyāna - meditation

- sāmādhi - absorption

While hatha yoga describes an almost mechanistic approach to the awakening and ascent of kundalinī, all forms of yoga (karma, bhakti, jnāna) have a signifcant influence over kundalinī shakti. For instance, cultivating the feeling of unconditional love in bhakti yoga naturally awakens kundalinī without the practitioner’s focus on it.

Yoga Postures

While yoga asanas make one strong and flexible and balance the endocrine and nervous systems, the hatha yogi views āsana in terms of nādī purification to facilitate the joining of prāna and apāna in the sushumnā for its subsequent rise.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipikā mentions 84 postures with eight most important. The eight are mainly seated postures that allow the yogi to remain stable and comfortable to carry out the higher hatha practices of concentration, meditation, and absorption.

The ancient hatha texts also mention other postures found in contemporary yoga: the sitting forward bend posture paschimottanāsana, the backward bending “bow” posture dhanurāsana, the arm balancing “peacock” posture mayurāsana, and the spinal twisting posture matsendrāsana.

Nāda

As one progresses in hatha yoga, one’s inner life takes on a richness that draws the senses inward (pratyāhāra). Together, the senses concentrate the mind where it begins to discern inner sound vibration (nāda). This focus is delicate and transforms our state of consciousness. From it, our mind approaches pure silence where the expansion into divine consciousness can take place.

For this reason, we do not play background music in our courses. The addition of music in yoga class is a recent phenomenon introduced by Western teachers out of ignorance. External stimuli, no matter how pleasant, conflict with the intensification and deepening of this subtle inner focus. A mind oscillating back and forth between internal and external stimuli is not concentrated enough to settle deeper into higher meditative states. From the Yoga Sutras:

Tat-pratishedhaartham eka-tattvaabhyaasah

Commentary: The seeker should focus his mind on one specific object of concentration. If he jumps from one to another, steadiness of mind can never be developed. Not only must concentration be focused on one object alone during any given sitting, it is the only way to gather the rays of the mind and to perfect one-pointedness.

Music can guide concentration towards meditation when it is the only focal point of the mind as in Nada Yoga where one consciously listens to musical notes in the Indian scale which resonate at the vibratory level with the chakras. One also repeats mantras which are sound vibrations that protect the mind (manas=mind, tra=protect). Mantras quell indiscriminate thought activity and bring us closer to that mental silence conducive to meditative states.

Hatha Yoga Lineages

Sivananda Yoga, Vinyasa Krama Yoga, and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga are systems of Hatha Yoga taught at La Source. Each system has developed through a specific lineage: Sivananda through Sivananda Saraswati of Rishikesh and Vinyasa Krama and Ashtanga Vinyasa through Krishnamacharya of Mysore.

When you come to any of our hatha yoga courses, they include the structured posture sequence of that specific hatha system. Some include prānāyāma breathing exercises. Others may not include prānāyāma as a stand-alone practice but focus your attention to the breath during postures to regulate the prāna and to intensify concentration. Some teachers may include meditation.

There are many more Hatha Yoga systems which are either named after the master of that hatha system or after a yogic concept to set it apart.

Where you find classes generically named “hatha yoga”, the teacher is either not certified through a specific lineage or is certified but chooses not to adhere to that lineage’s structured sequencing of yoga postures. The teacher may wish to come up with his/her own sequence of the classic postures or create a sequence that will suit the specific needs of the students.

- Read: "Raja Yoga and the Mind"

- Read: "Tattva Boddha: to realise the divine"

Test your Yoga Vocabulary

Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Jnāna Yoga, Rāja Yoga, Hatha Yoga, Prāna, Apāna, Nādī, Idā – Pingalā - Sushumnā, Chakra, Kundalinī, Granthī, Yamas, Niyamas, Kriyā, Mudrā, Bandha, Āsana, Prānāyāma, Pratyāhāra, Dhāranā, Dhyāna, Sāmādhi, Nāda

Bibliography

- Yoga Yājnavalkya, commentaries by A.G. Mohan

- Hatha Yoga Pradīpikā, commentaries by Swami Muktibodhananda

- Siva Samhitā, commentaries by Srisa Chandra Vasu

- Gheranda Samhitā, commentaries by Srisa Chandra Vasu

- Hatha Yoga Pradipikā, commentaries by A.G. Mohan

- Swara Yoga, Swami Muktibodhananda